Section 202(a) of the Executive Order charges the U.S. Environmental Protection agency with making recommendations to “define the next generation of tools and actions to restore water quality in the Chesapeake Bay and describe changes to be made to regulations, programs, and policies to implement these actions.”

Water quality is the most important measure of the Chesapeake Bay’s health. For the Bay to be healthy and productive, the water must be safe for people and support aquatic life, such as fish, crabs and oysters. The water should be fairly clear, have enough oxygen, contain the proper amount of algae and be free from chemical contamination. Currently, excess nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment lead to murky water and algae blooms, which block sunlight from reaching bay grasses and create low levels of oxygen for aquatic life. In 2008, water quality was again very poor, meeting only 21 percent of the goals established in the Chesapeake 2000 agreement. Discuss how to improve water quality on Facebook.

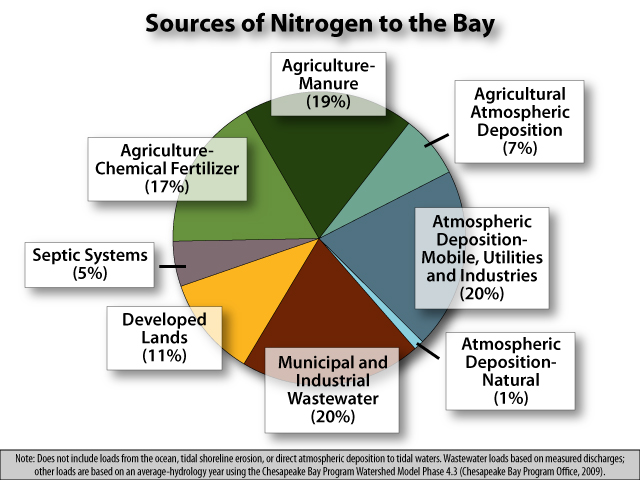

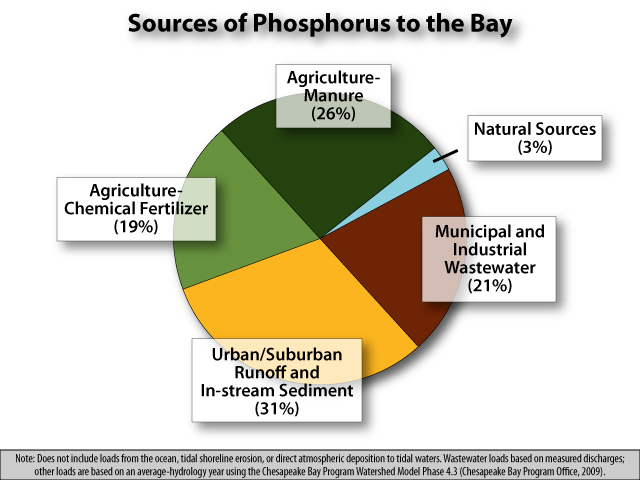

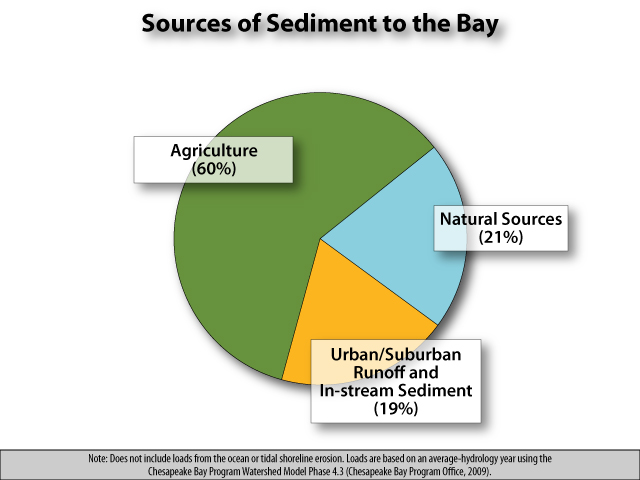

The main sources of pollution are agriculture, urban and suburban runoff, wastewater, and atmospheric deposition.

AGRICULTURE: Agriculture covers about 25 percent of the watershed, representing the largest intensively managed land use. There are an estimated 87,000 farms covering about 8.5 million acres. Agriculture is the greatest source of pollution to the Bay. While significant efforts and progress have been made, improperly applied fertilizers and pesticides still flow into creeks, streams and rivers, carrying excess nitrogen, phosphorus and chemicals into the Chesapeake Bay. Tilling cropland and irrigating fields can cause major erosion. Additionally, the nutrients and bacteria found in animal manure can seep into groundwater and runoff into waterways. Read more on the Chesapeake Bay Program website.

URBAN AND SUBURBAN LAND: Human development, ranging from small subdivisions to large cities, is a major source of pollution for the Chesapeake. There are about 17 million people living in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. In fact, because of the region’s continued population growth and related construction, runoff from urban and suburban lands, including septic systems, is the only source of pollution that is increasing. These areas are covered by impervious surfaces – such as roads, rooftops and parking lots – that are hard and don’t let water penetrate. As a result, water runs off into waterways instead of filtering into the ground. This runoff carries pollutants including lawn fertilizer, pet waste, chemicals and trash. Septic systems release pollution that eventually ends up in the water. Read more on the Chesapeake Bay Program website.

WASTEWATER: There is a tremendous volume of sewage that must be processed in the watershed. The technology used by the 483 major municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants has not removed enough pollution, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. Upgrading these facilities is now underway so they can remove more pollution from the water, but this effort will take time and is very expensive. As population growth increases, the need for wastewater treatment will expand and discharges will increase. Read more on the Chesapeake Bay Program website.

AIR POLLUTION: When pollution is released into the air, it eventually falls onto land and water. Even larger than the Chesapeake Bay’s watershed is its airshed, the area from which pollution in the atmosphere settles into the region. This airshed is about 570,000 square miles, or seven times the size of the watershed. Nitrogen from air pollution contributes to poor water quality in the region, and about half of the pollutants come from outside the watershed. Air pollution is generated by a variety of sources, including power plants, industrial facilities, farming operations and automobiles and other gas-powered vehicles.

Read more on the Chesapeake Bay Program website.

REDUCING POLLUTION: The Chesapeake Bay Program Office estimates that the maximum amount of pollution the Chesapeake Bay can receive annually and still meet water quality standards is 175 million pounds of nitrogen and 14.1 million pounds of phosphorous. For comparison, CBPO estimates that sources in the watershed delivered 311 million pounds of nitrogen and 19 million pounds of phosphorus to the Bay in 2008. Therefore, nitrogen loads would have to be reduced by approximately 44 percent and phosphorus loads by approximately 27 percent. The Chesapeake Executive Council has committed to implement all controls necessary to restore the Bay by no later than 2025.

The Chesapeake Bay Program’s computer model shows that reducing pollution loads to these levels will be more difficult than previously thought. Pollution reduction strategies previously developed by the states and District of Columbia would only reduce nitrogen to 244 million pounds and phosphorus to 21 million pounds (the Chesapeake Bay Program has not yet run updated scenarios for sediment).

To meet nitrogen target load of 175 million pounds nitrogen and 14.1 million pounds phosphorus means that pollution reduction practices would have to be applied to about 90 percent of available areas. Therefore, restoring water quality in the Chesapeake Bay will require improved technologies and approaches as well as significantly more widespread implementation of pollution reduction practices.

Additionally, reducing pollution will become an even greater challenge as population and development in the watershed increase. The population is expected to increase by almost 30 percent between 2000 and 2030, increasing wastewater loads. If current trends continue, impervious cover could increase 60 percent by 2030, leading to greater stormwater runoff. Pollution from agricultural may not decrease as fewer acres are in cultivation because the density of animals may increase. All of this means that strategies to achieve water quality standards must account for growth as well as address existing loads.

Watch EPA senior advisor Chuck Fox speak about the sources of pollution.